Robinson Spring, before earthwork began for the Rising Spring development

Sometime after 1820, in what is today Clinton, Mississippi, a local resident, or perhaps it was a frontier traveler, lost a pair of eyeglasses near the wilderness trail known as the Natchez Trace.

In the same vicinity, someone lost a clay smoking pipe. Someone else lost a thermometer with the degrees delineated in old English script. Other lost items included a sword scabbard, a crown-shaped English pin, a monogrammed silver spoon, a demijohn bottle, numerous coins and buttons, a worn-out hoe, a knife crafted by a Vicksburg silversmith, and several minié ball bullets, some of which had been fired while others were unspent.

Over time, all the items vanished into the underbrush or were buried under accumulating dirt, until two men came along, searching for telltale signs from the past — outcroppings of someone else’s life, and of history.

The relics, and what they revealed about previous, overlapping worlds, appear not to have factored into the planning of a massive earthmoving project that is currently underway at the relevant 54-acre site, for a $200 million mixed-use real estate development known as Rising Spring.

Yet for Clinton resident David Sullivan, the presence of the items — he has since found all of the ones described — offered important clues and conveyed a sense of continuity that is now coming to an abrupt end.

Sullivan, who grew up in Clinton and is an avid history buff and relic hunter, felt compelled to step in after he heard that multiple overlapping layers of local and state history were about to be ripped apart for the Rising Spring development. The project is being built on what is arguably the most historic site in town, and it appeared that someone needed to drive the preservation bus. So, Sullivan and a like-minded friend set out to find and preserve what they could of three centuries’ worth of artifacts hidden away on the land.

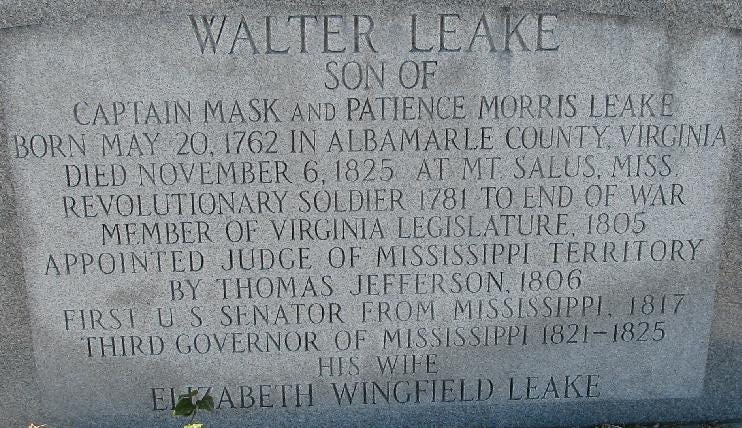

The core of the site was the original homestead of Mississippi’s third governor, Walter Daniel Leake, a Revolutionary War veteran who was also a territorial judge, a state supreme court justice, a member of the 1817 constitutional convention and one of the state’s two first U.S. senators. Near Leake’s house site was a second notable feature, a freshwater spring that had attracted travelers and residents for centuries. The overall area had been occupied or visited by people of both historical significance and everyday status since the territorial days. Now, surviving evidence of their lives lay in the path of the Rising Spring project.

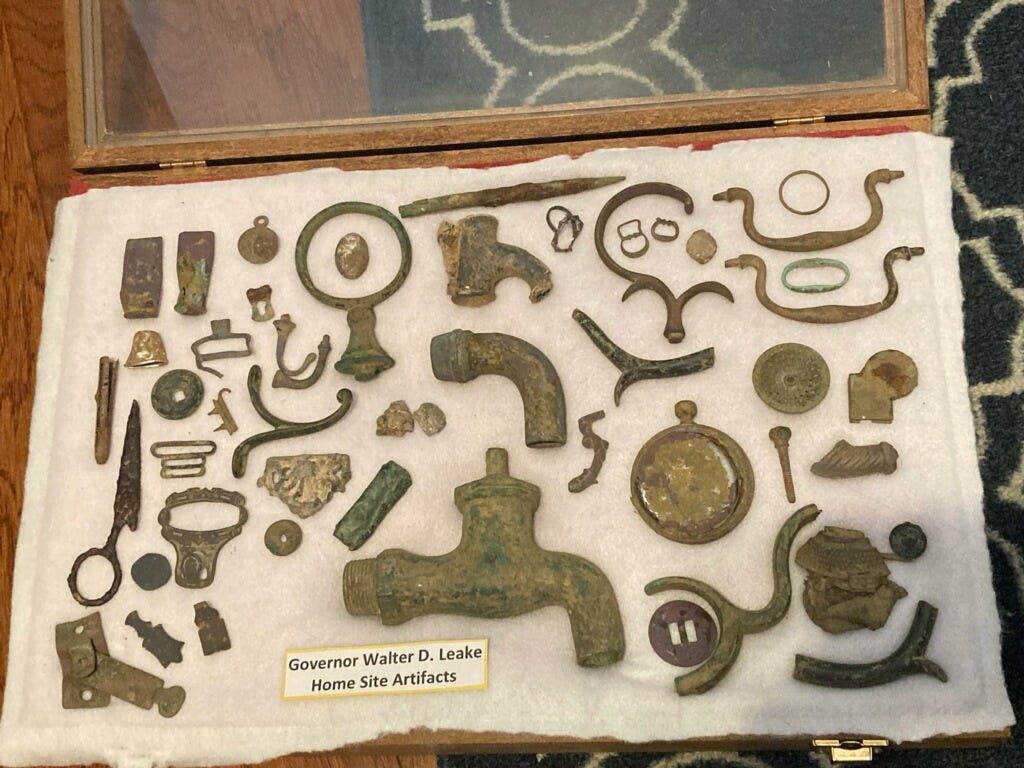

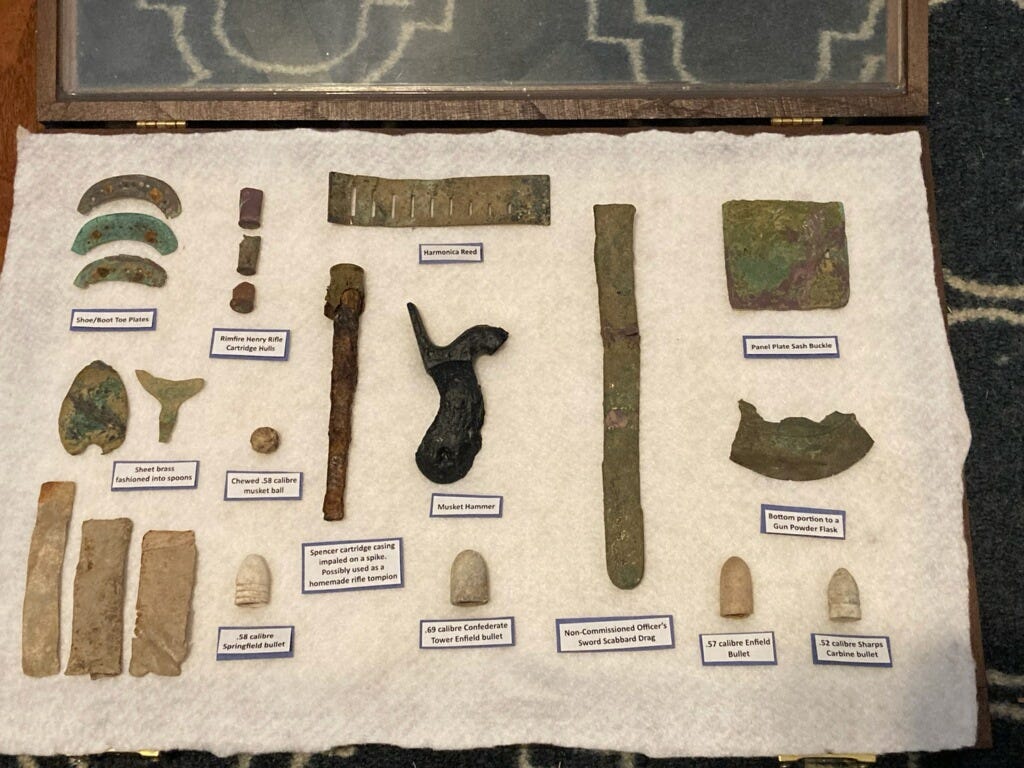

Sullivan said that because local officials showed no interest in surveying, much less exhuming the relics that underlay the site, he and his friend began methodically probing the earth with metal detectors and shovels. Along the way, they discovered a motherlode of museum-quality artifacts that otherwise would have been destroyed or buried so deeply they would likely never be seen again. Sullivan is currently in the process of cleaning, researching and curating everything he has found.

To the untrained eye, the parcel of land bounded by I-20, U.S. 80 and Springridge Road was an unremarkable, undeveloped remnant wedged between a hodgepodge of unplanned shopping centers. Clinton is more or less a suburban traffic jam of a town, with a scattering of historical markers and a core historic district that goes by the quaint sobriquet Olde Towne. Local leaders are ever attuned to opportunities for residential and commercial growth, and although the Rising Spring site would have been suitable for a park, their focus was on its economic development potential. The result was the planned mixed use real estate development, undertaken by the city of Clinton and Mississippi College. When the official Rising Spring groundbreaking ceremony took place almost three weeks ago, earthmoving equipment was already leveling the trees and rolling hills, and Sullivan and his buddy were deep into their historical triage.

Sullivan said that when he first approached the developer about probing the site, he was given permission with the disclaimer that there was “nothing of historical value there.” Sullivan said he scoffed at that assessment. The project’s backers appear to have not applied for any permits from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History because none of the sites was officially registered — or, at least, there is no record of their having done so in MDAH subject files reviewed for this article, nor any record of a recent recommendation that they do so (it’s possible that federal permits were required that were granted based on previous MDAH recommendations). The last time MDAH employees had visited was in the 1980s, according to departmental records, and that was only to the section that included what was known as Robinson Spring. One structure on the property, the Ashford house, which was built on the site of the original Walter Leake mansion by one of his heirs, was deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 2020, but MDAH’s Sam Wigglesworth noted recently that it was “presumably nonextant.” In fact, the columned, two-story house, surrounded by landscaped grounds, was quietly demolished to make way for Rising Spring.

The artifacts that Sullivan unearthed as the bulldozers rolled spanned the decades from the 1700s to the 1980s, with key figures related to the Revolutionary War, the Mississippi Territorial era (1798-1817), the War of 1812 and the Civil War. The historical core was Mt. Salus, the former slave plantation that Walter Leake established during the early 19th century along the Natchez Trace. Leake’s Mt. Salus home and the later Ashford house stood on a high hill just east of Robinson Spring, which featured prominently in Clinton’s early history, when the town was likewise known as Mt. Salus. Leake was living in Mt. Salus at the time of his death in 1825, soon after his reelection as governor. His family and heirs continued to occupy the dwelling until it burned in the 1920s.

Around 1950, one of Leake’s heirs built the Ashford house, which was designed to mimic Mt. Salus on the same site. Few contemporary travelers along busy Springridge Road likely took much notice of this historical redux, tucked away in a grove of old trees and flowering shrubs at the end of a circular drive, which was still controlled by family members under the auspices of Ashford Acres LP. Though the world has dramatically changed around it multiple times, the placeholder at 444 Springridge Road held its ground until the demolition crews and bulldozers arrived.

After the house was razed, earthmoving equipment and sawyers cleared the area, including a line of live oak trees planted years ago in an attempt to beautify otherwise commercially cluttered Springridge Road. Rather than retain the landscaping as adornments to the new built environment, the developers went for a clean slate. Only the small Leake family cemetery remains untouched, for now, in a copse of trees on the property’s northeastern edge.

To the west, the artesian outflow known as Robinson Spring, which was originally named Swafford’s Spring, was a notable feature of the larger site. The spring’s abundant cold, clear water had attracted Native Americans and provided a way station for frontier travelers between Nashville and Natchez, and later, for Union and Confederate troops. It was reportedly the most powerful of several springs scattered through the area and continued to supply residents with drinking water through the 1920s. A YouTube video posted by a local in 2021 shows water burbling from within a circle of old, mossy brickwork, in a verdant ravine of ferns, elephant ears and magnolia trees – all of which have since been obliterated. The developers have said they intend to incorporate the spring into the Rising Spring footprint – hence, the allusion in the name, but their slash-and-burn approach has already eliminated its historical context and natural setting. Sullivan speculates that some of the brickwork dated to the 1820s, but observed, “Now it just looks like a hole with water.”

Sullivan’s own approach to digging at historic sites is primarily forensic. He seeks to answer the question: What happened here? He is clearly a collector, but he seems genuinely curious about what each recovered item says about its era and about past lives, and researches his finds, then fashions them into displays, organized and identified by location.

Clinton, which is Sullivan’s home turf, is a city of 28,000 founded as Mt. Salus in 1823 at the intersection of the Natchez Trace and the Jackson-Vicksburg Road, which was built to connect the state capital with the Mississippi River. The WPA Guide to the Magnolia State, published in 1938 by the federal Works Progress Administration, devotes considerable space to Mt. Salus and Robinson Spring, as well as to the nearby ruins of the home of another Revolutionary War veteran, Gen. Raymond Robinson, the presumed site of which was similarly destroyed in the late 1990s for the headquarters of the Fortune 500 company WorldCom. (Clinton’s mayor, Phil Fisher, directed questions about the historical sites to an assistant, who did not respond.) According to the WPA guide, the town that eventually became Clinton was originally an Indian agency known as Mt. Dexter; around 1812, Leake, while a territorial judge, “bought land here and later erected a home called Mount Salus. The white settlement that grew up around his home was called Mount Salus. The first land office and the first post office in the State were in this place.” In other words, the site being leveled for Rising Spring was the nexus of modern Clinton.

A few of the claims associated with the sites, in published reports and even historical records, are difficult to verify and, in some cases, questionable. For example, Leake’s house was likely the first brick home in Hinds County, but it was not the first in the entire state, as is sometimes claimed (including in the postcard previously pictured in this story). Likewise, construction dates ascribed to Robinson’s house seem too early, according to a Department of Archives and History historian. All of which makes physical artifacts like those that Sullivan has unearthed even more important.

Residents of Mt. Salus changed the village’s name in 1828, reportedly in tribute to New York’s Gov. De Witt Clinton, for reasons that are not altogether clear (Gov. Clinton, who was credited with pushing through the construction of the Erie Canal, died that year). A railroad came through town three years later, after which Clinton boomed. The fact that the town had missed being selected the state capital by one vote rankled residents and is occasionally still mentioned today. One existing thoroughfare is the hopefully named Capitol Street, which terminates near Robinson Spring.

Leake’s Mt. Salus house, described in detail in a Mississippi Preservation blog, was reportedly damaged by soldiers of Gen. U.S. Grant during a raid from Vicksburg to Jackson in 1863. The same account notes that, “Towards the east a short distance from the house is the high, brick-walled burying-ground” where Leake, his wife, daughter and other family members are buried. Today, the cemetery, which includes a comparatively recent iteration of Walter Leake’s tombstone, is the only surviving node of the original Mt. Salus landscape, overlooking a Walgreens at the intersection of U.S. 80 and Springridge Road. Aside from the cemetery, every physical vestige of Leake’s chosen spot, including its physical topography, is gone.

A Virginia genealogical account includes an interesting anecdote about Leake: that while on his deathbed, he was unable to meet with the Marquis de Lafayette during the famous French general’s visit to Mississippi as part of his grand American tour in 1824-1825. Because he was too sick, Leake sent an emissary, who reported back that Lafayette recalled meeting him during the American Revolution. According to the account, when Lafayette was commanding Continental Army troops in the decisive Siege of Yorktown in 1781, he had met Leake and was impressed that the 17-year-old had run away from home to join the revolutionary contingent. A 1978 article in the Journal of Mississippi History repeated a questionable related anecdote – that Lafayette had been entertained at Leake’s Mt. Salus home during his “triumphal tour” (half a century after the revolution) and that, “For many years the carriage in which he was said to have ridden, the bed in which he slept, and other furnishings which he used were preserved and pointed out until they, along with Mt. Salus, burned about 1920.”

By the late 1930s, when the WPA writer passed through, the site of Leake’s Clinton home still commanded the northernmost of a pair of high hills, the other being the site of Raymond Robinson’s home. The unnamed writer observed that the road between the two had been the setting for a duel in 1829 between a local judge, Isaac Caldwell, and the state legislator who had cast the deciding vote that prevented Clinton from being designated the capital. Both men survived, though Caldwell was later killed in an unrelated duel in the county seat of Raymond, which was named for Raymond Robinson. The Robinson home, built “before 1810,” was abandoned by the time the WPA writer visited, but the guide reported that in 1818, Andrew Jackson, a famous general in the War of 1812, then the land commissioner in Clinton and later a U.S. president, had visited there.

Writer Eudora Welty took the photo of the house in the WPA guide (below) while roaming around Mississippi, also in the employ of the WPA, which she captioned in her book One Time, One Place, “House abandoned/Old Natchez Trace, near Clinton.” Tantalizingly, the WPA guide notes: “Here the wealthy widow of Judge Caldwell was found murdered shortly after her re-marriage.” The volatile Caldwells, one guesses, were a riveting topic of conversation in the 19th century town (some accounts say the Caldwells’ house was a separate structure that stood between Robinson’s and Leake’s homes).

According to a 1988 newspaper article, Robinson Spring was noted in a survey conducted in 1802-1803 for the purpose of improving the Natchez Trace for travel. In 2005, a local historian asked the Department of Archives and History to assess its eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places, due to plans to widen U.S. 80, but the agency’s then-program supervisor, Richard Cawthon, responded that he did not have “sufficient interpretive context” to propose listing it. As a result, the spring today seems to have no official protection. Archives did include the Ashford house in its 1970 survey of the state’s historic structures, and in response to a 2014 request from an environmental consultant for a review of 45 acres of the Ashford property, recommended that a cultural resources survey be done by a qualified archaeologist and that the review take into account the impact of a development project on the then-extant Ashford house. It is not clear whether such a review was ever done — if so, it was not included in the Archives subject file. It is also possible that such a review would not be publicly available because archaeological sites are subject to being plundered.

There is no indication that the Robinson house site was probed for relics, as Sullivan is doing at Mt. Salus. When the overall site was graded for WorldCom’s headquarters, the family cemetery was dug up and removed to another burial ground to make way for a parking lot. Parts of the property had previously been bulldozed during the construction of I-20, making it unclear precisely where the main house stood. WorldCom’s corporate history eventually ended in scandal and bankruptcy, with its CEO and its CFO going to jail, at which point Clinton lost its claim to being the smallest city to host a Fortune 500 company.

Clinton’s long aspirational bent and spotty preservation ethos meant that the undeveloped Mt. Salus and Robinson Spring sites, owned by Mississippi College, Ashford Acres, Clinton Parkway Development LLC, and GB Holdings LLC (based on Hinds County land records), were viewed primarily through the prism of economic development. A July 30, 2024, news release noted that in addition to land clearing and leveling, college officials were working with the state Department of Transportation on a plan “to improve infrastructure, including a parkway-like roadway, traffic light relocation, pedestrian enhancements, lighting and landscaping.” The goal was to create “a cultural destination to rival anything currently available across the state of Mississippi,” according to Mississippi College’s president, Blake Thompson, who called Rising Spring a “historic project” – an apt descriptor, in more than one way.

Another news release described the development’s centerpiece as “a historic spring and canopy of trees preserved as an inviting ‘green space’ for pedestrians.” Placing “green space” within quotation marks proved telling: Though a section of woods still stands to the south, by mid-August the canopy of trees around the spring had been bulldozed, leaving behind acres of bare dirt dotted with a handful of younger trees, encircled by sediment-retention fences. An artist’s rendering of Rising Spring’s phased developments shows a water feature, though it is not known whether it might tap the flow of the spring, assuming the flow continues following the massive land disturbance.

Sullivan said he is hopeful that some parts of the site, including in the vicinity of the spring, might still yield buried artifacts, but time is running out. The site of Mt. Salus has been scraped down perhaps 20 feet, and its former cisterns and wells bulldozed into ravines and buried. Many remaining artifacts have either been crushed beneath the tracks of heavy equipment or interred under tons of displaced ground.

After providing photographs of a small sampling of his finds, Sullivan observed that the artifacts represent key surviving evidence of everything that has happened on the sites. But, he added, there’s no way to know how many other clues in the historic fabric have been lost.

Images: Robinson Spring in 2021 (screencap from SuperDaveVideos/YouTube); artifacts from Mt. Salus site (courtesy David Sullivan); Mt. Salus house (Mississippi Department of Archives and History postcard collection); Ashford house (Google Earth); former site of Mt. Salus (author); Walter Leake tombstone (FindAGrave.com); ruins of Raymond Robinson home (Library of Congress); artist’s rendering of Rising Spring (via RisingSpring.com); artifacts from Mt. Salus (courtesy David Sullivan)

Such interesting history and so frustrating to once again have modern commercial development trample over the preservation efforts of individuals. Thanks for sharing this.

Great research and writing. Thanks!